Finding inspiration in Dipa Ma, the “patron saint of householders”

In 2019, I met with my meditation teacher Michael Taft and told him about a few difficulties that I experienced in my practice. First, I felt emotionally blocked up - even though I practiced formal heart-centered meditations like Metta (loving-kindness meditation) or Tonglen (compassion meditation), I didn’t feel as loving as I had in the past. As a new mom, I found this especially upsetting. I had expected the transition to fill me with maternal love so profound that it would extend to all living creatures, human and not, and was disappointed that it had not. (I’ve always been excellent at unrealistic expectations and self-criticism). Second, I felt a disconnection between my practice on the cushion and the rest of my life. I knew that compartmentalizing “practice" and “life” stood counter to what I wanted: to live a mindful and openhearted life. I felt stuck and didn’t know how to integrate. Third, as a mom of a young toddler who was also attempting to cofound a startup at the time (me, not the toddler), I felt unfocused - my attention felt scattered and diluted. So I sought out Michael’s wisdom on these fronts.

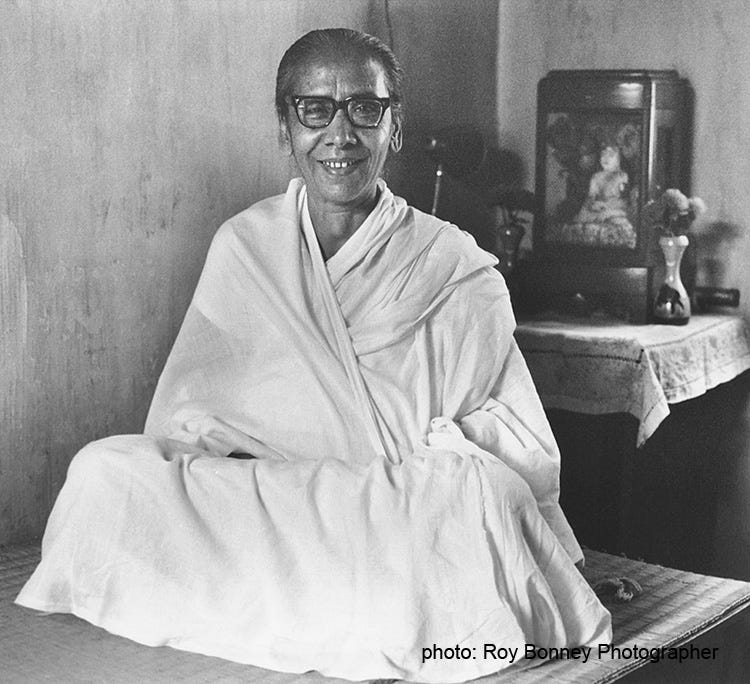

In response, Michael told me about Dipa Ma, a Buddhist master from Calcutta who died in 1989 after teaching some of the most influential Western teachers - Jack Kornfeld, Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzberg, and Sylvia Boorstein to name a few. He thought that learning about Dipa Ma and how she taught could inspire me to change my relationship with daily life. He was right. While I wouldn’t say that learning about Dipa Ma has completely transformed my practice, it has massively enhanced the time I spend with my child, and that’s what I would like to write about here.

Dipa Ma lived in Calcutta during a time when women were not commonly encouraged to pursue formal meditation practice. She began to practice insight-mindfulness meditation in her 40s during a difficult time following her husband’s death. As many great teachers do, she must have had tremendous spiritual talent and progressed quickly to reach enlightenment. People who met her describe her as deeply peaceful and deeply loving. Even more remarkable than her fast progress was her approach with students. Dipa Ma worked with Indian women who raised children and worked in the home - as you can imagine, these are women who hardly had much free time for leisurely practice. She taught her students that anything could constitute meditation if approached mindfully. Laundry, cooking, cleaning, tending to the children - whatever the task, it can be performed with sharp awareness. She showed these women how to be vividly present in their daily lives, and her approach turned out to be wildly effective.

Suddenly, Indian women who had lacked access to spiritual teachings and practice were waking up amid their so-called ordinary lives. When someone truly internalizes the attitude that all of life is practice, they may quickly find themselves practicing for hours and hours every day. And ultimately, isn’t this what practice aspires to be? Seamless integration of mindfulness into daily living, in striking contrast to the partition I complained about to Michael?

Here is one approach to bringing the spirit of Dipa Ma to time with our children, which has been a source of significant benefit my life. First, set an explicit intention to parent as a practice. John Yates, Ph.D. (also known as Culadasa), a neuroscientist and meditation teacher, writes extensively about the importance of holding correct and strong intentions in meditation. He goes so far as to argue that strong and precise intention is actually all that we do in meditation. In his book The Mind Illuminated, he illustrates this through the example of a child learning how to play catch. Knowing how to move one’s arm to catch the ball is not consciously learnable; instead, the child holds an explicit intention of learning to catch while practicing again and again, until more unconscious parts of the brain learn the skill seemingly on their own. The same can be said for meditation - if we consciously pursue the steps of meditation, we often trip ourselves up. Instead, we hold conscious intentions and an attitude of firmness-but-kindness with ourselves, and our intentions begin to shape our experience.

From that perspective - that setting and holding intentions is the meat of practice - it’s important to elaborate a bit upon that intention. It’s useful to build it out conceptually in sufficient detail so that we know when we’re off-target and need to recommit to the intention. Here are some factors of the intention I hold as I do this:

1. Full presence. When we realize we’ve become distracted by our thoughts, to-do lists, the radio, whatever - we bring the attention back to our children. Of course, sometimes we need to multitask, but often we multitask without really needing to, thereby losing opportunities for actual presence in our lives.

2. Awareness of what we’re doing. Buttoning the child’s shirt, we notice the button in our fingers, and the movement required to complete the task. Bringing a spoon of food to the child’s mouth, we pay attention to how we move our fingers, wrists, and arms.

3. Attention to our senses. Feeding our child, we attend to the sight of the child’s little mouth closing around the spoon, to the expression the child makes in reaction to the food, to the sound of the chewing and swallowing. Singing a song with our child, we pay attention to the sounds and the sensations in our mouth and throat. For me, sometimes this one means just looking at my little girl’s cute little face and savoring the details of its features and expressions.

4. Attention to the content of the experience. We pay attention to how a baby lifts and manipulates his toy, to the idea our toddler attempts to communicate, to an older child’s verbal and facial expressions, as well as to our reactions to all of these things. When we find ourselves tuning out, we bring ourselves back to the content.

5. Fully experienced emotions, especially those you want to cultivate and reinforce, like affection, compassion, or sympathetic joy. Extend them, notice how they feel throughout your body, and invite them to sink in. Pay attention to associated sights (the appearance of your child’s smile), bodily sensations (warmth, tingling, pleasurable pressure), and thoughts the accompany the emotion (but don’t get lost in the thoughts, just notice them and return to being fully present).

It’s useful to have some ideas of what it means to be mindful while spending time with our child, but if the above is too convoluted, just remember this: pay attention to what you’re doing and give it your full presence. I hope that Dipa Ma, who helped many householders find spiritual peace through mindfulness in daily life, can inspire others to treat their time at home and with their children as an opportunity for presence and depth.